Why monetary policy should crack down harder during high inflation

by Peter Karadi, Anton Nakov, Galo Nuño, Ernesto Pasten and Dominik Thaler[1]

Inflation and price flexibility

The recent surge in inflation across Europe, the United States and other countries raises an important question: should monetary policy respond differently during high inflation episodes than in more “normal” periods? There is growing evidence that the answer is yes. When inflation is higher, prices change more frequently – in fact the frequency more than doubled during the recent inflation spike (Montag and Villar, 2023; Cavallo, Lippi, and Miyahara, 2023). More frequent changes increase the flexibility of prices, which enhances the effectiveness of monetary policy. The more flexible prices are, the “cheaper” it is for the central bank to reduce inflation in terms of the overall impact on economic activity.

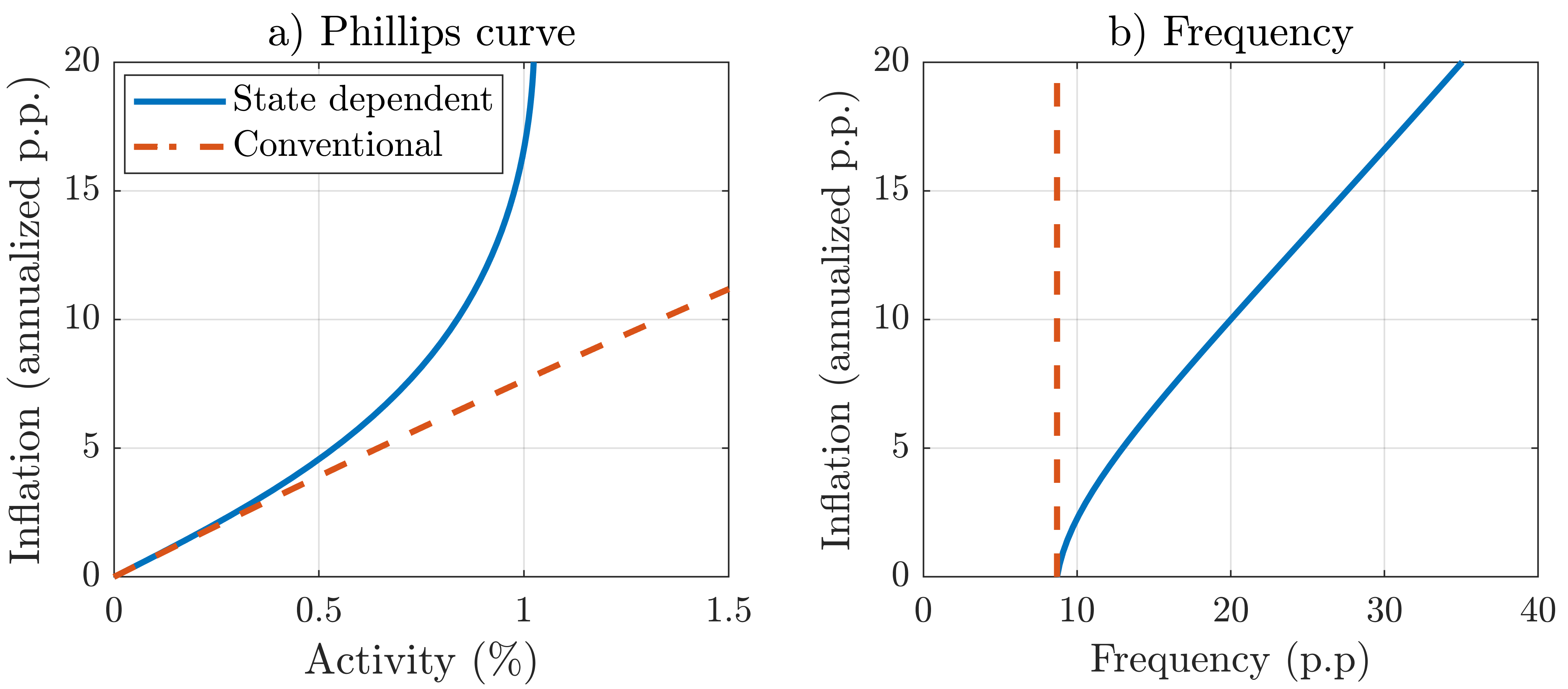

In conventional models of monetary policy (Woodford, 2003; Gali, 2008), the frequency of price changes – and, thus, price flexibility – is assumed to be constant. This implies that monetary policy has a similar effect on output and inflation regardless of the inflation environment. As a result, the relationship between inflation and economic activity (captured by the Phillips curve) is approximately linear (see the dashed red line in Chart 1, panel a). However, these models are unable to capture the higher frequency of price changes in high inflation environments (as shown in panel b). In contrast, models with state-dependent price-setting, where the frequency responds endogenously to economic conditions, as the blue solid line in panel b) illustrates, can capture this phenomenon (e.g. Golosov and Lucas, 2007). They also imply a state-dependent variation in the effectiveness of monetary policy. In high inflation periods, when prices are more flexible, monetary policy becomes more effective in reducing inflation without dealing a significant blow to economic growth. As a result, state-dependent models predict a non-linear relationship between inflation and output, as the solid blue line in Chart 1, panel a) illustrates. Recent empirical evidence supports this prediction (Cerrato and Gitti, 2023; Benigno and Eggertsson, 2024).

Chart 1

The Phillips curve and the frequency of price changes

(activity: percentage deviation from efficient level; inflation: percentage points, annualised; frequency: percentage points)

Notes: Panel a) depicts the trade-off between inflation and activity (measured via the output gap), which monetary policy faces. The solid blue line shows the results of the more realistic state-dependent model, whereas the dashed red line shows the results of the conventional model under the assumption of a constant repricing frequency. In the state-dependent model, monetary policy tightening in a high inflation environment can have a larger impact on inflation, with less damage to overall economic activity. Panel b) displays the relationship between the frequency of price changes and inflation in the conventional model (dashed red line) and the state-dependent model (solid blue line). In the state-dependent model, higher inflation is accompanied by a higher frequency of price changes.

Optimal monetary policy: strike while the iron is hot

How does the response of the price change frequency to inflation affect the optimal conduct of monetary policy? In conventional models with a fixed frequency, two key conclusions emerge. First, monetary policy should offset excess demand shocks, such as spikes in government spending, which would otherwise drive output over its potential. This would help to stabilise both inflation and economic activity. Second, policy should “lean against” cost-push shocks equally strongly in both high and low inflation environments because the trade-off between inflation and output remains constant.

How are these conclusions affected when the price change frequency varies, and the Phillips curve is non-linear? Our research (Karadi, Nakov, Nuño, Pasten and Thaler, 2025) explores this question using a state-dependent price-setting model. We show, first, that excess demand shocks should still be offset as prescribed by the conventional model. The reason is that in such cases monetary policy can simultaneously stabilise both inflation and activity.

Second, however, we find that the monetary policy response to cost-push shocks should be more aggressive in high inflation periods, a recommendation which is absent from the conventional model. This is because during these periods inflation can be curtailed with a smaller impact on economic activity. In other words, monetary policy should “strike while the iron is hot”. Chart 2 shows the relationship between inflation and activity under optimal monetary policy during cost-push shocks. The dashed red line shows that the relationship is approximately linear in the conventional model, implying similar policy prescriptions in both high and low inflation environments. The solid blue line shows the relationship in a model with state-dependent pricing frequency. In this case, the relationship is non-linear, and the slope is flatter in high inflation environments, implying that optimal policy takes a more aggressive anti-inflationary stance.

Chart 2

Inflation and economic activity under optimal policy

(activity: percentage deviation from the steady state; inflation: percentage points, annualised)

Notes: The chart depicts the relationship between inflation and activity (measured via the output gap) during cost-push shocks of varying sizes under optimal monetary policy. In a high inflation environment, monetary policy should stabilise inflation relatively more according to the state-dependent model.

Why should monetary policy lean harder against inflation when it is high?

When prices are more flexible, monetary policy action to combat inflation becomes less costly in terms of lost output, making a “soft landing” for the economy easier to achieve. The steeper Phillips curve during high inflation periods indicates that central banks can reduce inflation while incurring less economic pain than during normal times. Our research shows that it is indeed the non-linear Phillips curve that mostly accounts for the policy prescriptions of the state-dependent model. The relative welfare costs of inflation versus economic underperformance are similar in the state-dependent model and the conventional model.

Conclusions

Our findings suggest that central banks should adapt their approach to monetary policy during periods of high inflation. More aggressive policy measures can be implemented, taking advantage of the fact that the cost of reducing inflation is lower, in terms of lost output, when firms adjust their prices more frequently. However, as inflation decreases, monetary policy tightening becomes more costly again.

References

Benigno, Pierpaolo and Gauti B. Eggertsson (2023), “It’s Baaack: The Surge in Inflation in the 2020s and the Return of the Non-Linear Phillips Curve”, NBER Working Papers, No 31197.

Blanco, Andres, Corina Boar, Callum J. Jones and Virgiliu Midrigan (2024), “Non-linear Inflation Dynamics in Menu Cost Economies”, NBER Working Papers, No 32094.

Cavallo, Alberto, Francesco Lippi and Ken Miyahara (2023), “Large Shocks Travel Fast”, NBER Working Papers, No 31659.

Cerrato, Andrea and Giulia Gitti (2023), “Inflation Since COVID: Demand or Supply”, unpublished manuscript.

Galí, Jordi (2008), Monetary Policy, Inflation, and the Business Cycle: An Introduction to the New Keynesian Framework, Princeton University Press.

Golosov, Mikhail and Robert E. Lucas Jr. (2007), “Menu Costs and Phillips Curves”, Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 115(2), pp. 171–199.

Karadi, Peter, Anton Nakov, Galo Nuño, Ernesto Pasten and Dominik Thaler (2025), “Strike while the iron is hot: optimal monetary policy under state-dependent pricing”, Working Paper Series, ECB, forthcoming.

Montag, Hugh and Daniel Villar (2023), “Price-Setting During the Covid Era”, FEDS Notes, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System.

Nakamura, Emi and Jón Steinsson (2010), “Monetary Non-neutrality in a Multisector Menu Cost Model”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 125(3), pp. 961–1013.

Woodford, Michael (2003), Interest and Prices: Foundations of a Theory of Monetary Policy, Princeton University Press.

Distribution channels: Banking, Finance & Investment Industry

Legal Disclaimer:

EIN Presswire provides this news content "as is" without warranty of any kind. We do not accept any responsibility or liability for the accuracy, content, images, videos, licenses, completeness, legality, or reliability of the information contained in this article. If you have any complaints or copyright issues related to this article, kindly contact the author above.

Submit your press release